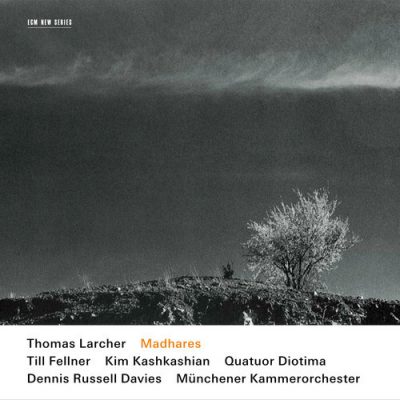

Thomas Larcher: Madhares

Till Fellner (piano), Kim Kashkashian (viola), Quatuor Diotima, Dennis Russell Davies (conductor), Munich chamber orchestra

© ECM 2010Reviews

Works

Boese Zellen for piano and orchestra (2006/rev.2007)

Sehr langsam, attaca

Langsam, attaca

Viertel ca. 83, attaca

Viertel ca. 77

Still for viola and chamber orchestra (2002)

Ruhig fließend – schneller, attacca

Ruhig fließend – schnell – ruhig fließend

Madhares for string quartet (2006/07)

I Madhares (Andante)

II honey from Anopolis (Adagio – attacca;)

III sleepless 1 (attacca:)

IV sleepless 2 – Madhares (Very fast)

V a song from? (Allegretto)

The creative output of Austrian composer (and pianist) Thomas Larcher (born 1963) whom the London Times recently called “a musical talent of unbounded sensitivity and distinction bound for 21st century glory” has been championed on ECM New Series since 2001. Last fall Larcher’s piano piece What becomes attracted wide-spread attention when premiered on Leif Ove Andsnes’ international tour with the project Pictures, Reframed in which musical performances were juxtaposed with video images by concept artist Robin Rhode. In the Daily Telegraph Ivan Hewett spoke of “a real 21st-century picture of childhood, rudely energetic and unsentimental”. Madhares, the thrid release dedicated exclusively to Larcher’s works, assembles some of the finest ECM musicians such as Kim Kashkashian, Till Fellner and the Munich Chamber Orchestra conducted by Dennis Russell Davies to present a gripping cross-section of Larcher’s recent orchestral output, enhanced by the third string quartet Madhares which is played by the youthful French Quatuor Diotima. Larcher’s recent pieces are marked by intense sonic imagination, great rhythmic energy and a virtuoso impact that makes for an immediately rewarding listening.

quoted from: www.ecmrecords.com

Thomas Larcher in Conversation with Anselm Cybinski

Anselm Cybinski: Would you say this recording marks a particular stage in your career as a composer?

Thomas Larcher: Well, in a sense every new release is a record of the latest stages you have passed through. While the first two albums I made with ECM, Naunz (2000) and IXXU (2006), presented works for smaller ensembles, in Madhares the focus has shifted towards music for solo instruments and orchestra. Still, written in 2002, could be regarded as the point of departure; Böse Zellen, written in 2006-07, marks a later stage in my pieces for larger forces – on the path towards the orchestral music I’m working on now, or that is already finished but hasn’t yet been premiered. And the quartet Madhares is my most recent foray into the world of chamber music.

Anselm Cybinski: The title Böse Zellen is taken from a movie, Still has associations with the idea of film stills, and the title of the quartet Madhares also seems to tap into the realms of optical impressions. How important are these visual connotations in your work?

Thomas Larcher: I can well imagine that my music evokes a range of images in the listener’s imagination, but for me personally I find the catalyst for my work in the ideas and realms of my own mind rather than sensory impressions. This catalyst is important to me, like an impulse or an electric charge, for what it does, rather than for its particular characteristics. So the title Madhares has less to do with the geographical region in the west of Crete than with a utopian place, somewhere far away from where I am – possibly completely beyond reach.

Anselm Cybinski: These new pieces clearly connect with genres such as the solo concerto or the string quartet that have such a long tradition in music history. To what extent are these traditions a source of that kind of an electric charge?

Thomas Larcher: For me, as a pianist, the concerto is very familiar territory, which naturally also prompts me to question it, above all by re-evaluating the primacy of the soloist. In both of the concertante works, in Böse Zellen and in Still, the orchestra is very active, more than just an accompaniment, so powerful that it often swamps the soloist.

Anselm Cybinski: Does the composer identify with the soloist? After all, you are also a pianist . . .

Thomas Larcher: Some people have described Böse Zellen as an “angry piece”, which maybe means that it reveals a layer of my personality that is not otherwise apparent in my day to day life. But that kind of obsession, manic activity, where “the wheels in your mind just keep on constantly spinning”, when you can’t stop your mind racing – I do know all of that very well. Yet, that’s not to say that the solo part should be equated with me as a person . . .

Anselm Cybinski: How would you describe your relationship to the instruments you have used here? – The “quiet” (silent?) viola, the prepared (masked) piano, not to mention that most noble of chamber music ensembles, the string quartet!

Thomas Larcher: Yes, for me the viola does emerge from silence, but there is also a certain roughness to its sound, an unprettified side, in deliberate contrast to all that elegiac expression that is so often associated with this particular instrument. As for the piano, that’s naturally a rather complex matter. On one hand there’s the escape from the brilliant to the masked piano sound, which is also very much about extending its coloristic spectrum. That’s why it was important to me to prepare it even more than usual by using a large ball and presenting the moment of “de-preparation” as a decisive juncture in Böse Zellen. And I’ve always been very interested in the percussive quality of the piano. On the other hand, for me the string quartet is and always has been the most exciting configuration of instruments, with the most associations, partly because it is so pure, partly because it has so unbelievably many different facets, even orchestral. The potential for sounds to merge seamlessly into each other only to become completely distinct voices again that you get in a quartet – that has to be unique. You just don’t get that kind of inwardness or that kind of tonal blend from a piano.

Anselm Cybinski: And could you perhaps tell us a little about working with Dennis Russell Davies?

Thomas Larcher: Dennis has been both a catalyst and a great source of encouragement to me, above all between 1997 and 2002 when he was artistic director of the Radio Symphony Orchestra in Vienna. He initiated Still, and saw it through to its premiere with Kim Kashkashian and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra. Böse Zellen is dedicated to Dennis; he has been one of the lodestars in my life as a composer, and was extraordinarily supportive during the whole recording process, for which I am very grateful indeed.

Anselm Cybinski: Who are your ideal listeners, when it comes to your own music?

Thomas Larcher: I have in mind a listener, who is familiar enough with the traditions of European classical music to recognise its various codes. Someone who can deal with structures and forms and yet who can enter into a sound world in a relatively naïve manner. I’m looking for a listener who in turn is looking for a dynamic relationship between the intellect and the emotions and can handle the ever-changing interaction of these two poles.

quoted from: www.ecmrecords.com